Fertiliser use many times leave deleterious consequences on the general environment. They are responsible for leaching and polluting groundwater, threatening aquatic ecosystems, and contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. In short, fertilizers pose a great threat to environmental sustainability. In 2011, up to 216 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent was released into the atmosphere because of production and use of urea alone. Urea is a nitrogen fertiliser which is an essential nutrient for plant growth. But this compound easily turns into gases that are over 260 times more dangerous than having carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. One would have thought, given the havoc that fertilisers wreck on the environment, why can’t we just get rid of them all at once? At least this should make our world a safer place. But it is not always that simple.

Why Fertiliser at all?

The need to apply fertiliser to soil comes from absorption of nutrients from soil by plants. When nutrients become insufficient in the soil, there is a need to replenish it. Worthy of note is that these nutrients are not only useful to plant. Humans also need them for growth. There are three primary nutrients or macronutrients: phosphorus, nitrogen and potassium. Phosphorus for example is essential to plant growth by supporting photosynthesis, respiration and energy transfer. It is important for bones and teeth formation as well in protein synthesis in humans. But soil loses phosphorus (and other nutrients) through the plant, air and water. Only 10-20% of the phosphorus that is applied to soil ends up being used by plants. For nitrogen it is about 30-40% while the rest stays in soil or diffuse into the atmosphere as highly toxic nitrogen oxides.

If we were to totally do away with the use of fertilisers now or in years to come, normal agricultural production can only feed about three billion people. This is because currently fertilisers support the production of 40-60% of our food. Without enough food to go round, food prices would increase and only those who can afford it will buy. This will definitely lead to a serious food insecurity problem and all the efforts to achieve a world without hunger would then only amount to vein. Essentially, this is pointing to the fact that fertiliser is very key to our survival. The only question that remains is how do we produce and use these nutrient sources without leaving the world a worse space.

Some Problems, Some Solutions

One of the reasons fertiliser use has become a problem is wrong application. Even though Africa applies the least fertiliser globally, many of the applications are done without knowledge of actual plant needs. It is like prescribing drugs to a patient without first testing them for what is wrong. For example a soil could need only little phosphorus, but what is available is a rigid NPK 15:15:15. Farmers may also use too many bags of a fertiliser thinking that the more use the more gain which is not always true. The solution to this is in the 4Rs of fertiliser management: right source, right rate, right place and right time. Farmers need to get their soils tested and mapped to know the soil nutrient needs per plot or hectare. This would mean that soil testing labs (or smart soil testing technologies) become available and easily accessible to farmers.

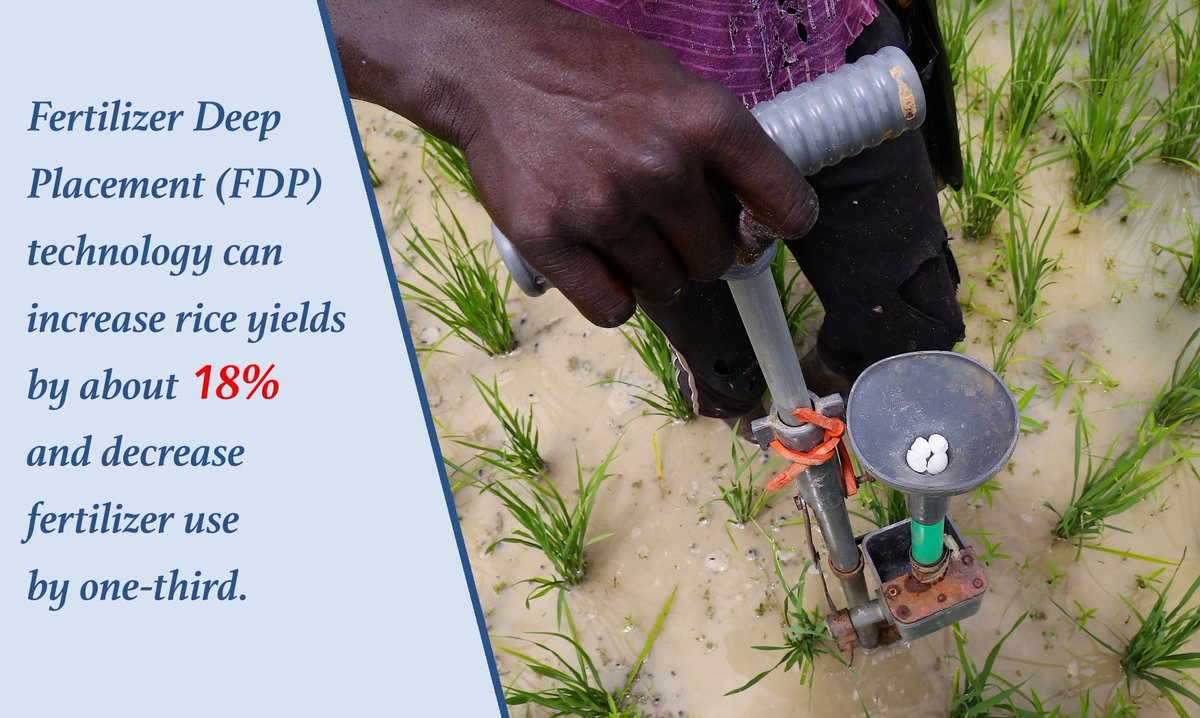

Then fertiliser blending plants that are flexible to individual needs of soils will be needed. When farmers test their soils and apply nutrients accordingly, it protects the environment and cuts energy and other excess expenses. One idea for fertiliser efficiency is Urea Deep Placement that involves dipping the mineral nutrient into the soil rather than leaving it on the surface to easily evaporate. This idea can increase productivity by up to 20% and reduce urea use about 30%. Another idea could be increasing the granular size of fertiliser blends so that it takes some time to decompose rather than have all the nutrients available at once.

Conclusion

It may sound crazy from an environmental perspective, but Africa will need to drastically increase its fertiliser use in years to come. More than 80% of the world population will be from developing countries in 2050. There will be less land and water available for farming to feed this overwhelming population. You can do the math and tell where the food will come from without fertiliser use. If the case is that we must increase fertiliser use with time in developing nations, the question we should ask henceforth is how to make fertiliser not the problem but the solution. The answer to this lies in bridging knowledge gap and developing technologies for efficiency and effectiveness in the fertiliser industry.